The second book in the project series, The Tug of the String: stories about staying connected, is just about ready for publication. (I’m waiting to get an awesome person to write the foreword). As if all three of you aren’t already salivating at the mere thought of this (yeah, not a lot of traffic on the site yet), here is one of the new stories.

Down to a great small sea

I went sailing last Tuesday, tacking out into a light breeze until the shore faded to a thin grey line. I had last sailed professionally when I was seven, captaining a tiny merchant vessel that plied the waves and troughs off the coast of New England. I had missed that work, the feel of spray on my face, the taste of salt on my lips, and the roll of the deck underfoot. It felt good to be back at the helm.

When I was very small I would often climb the wooded knoll behind our home in Connecticut and look east over the hills to the great Atlantic. The ocean would wink at me from its silver strand and I would long to be there, out on the great green sea, far from the sight of land, navigating by star-shots, moving goods from continent to continent, always on the lookout for rogue waves. But at seven, my prospects seemed dim, until I talked to Mom.

“I want to sail the ocean,” I said to her one day.

“Of course you do,” she said, wiping her hands on a dish towel. “And you shall. Let’s go.”

So hand in hand we walked down our driveway to the edge of a great small sea.

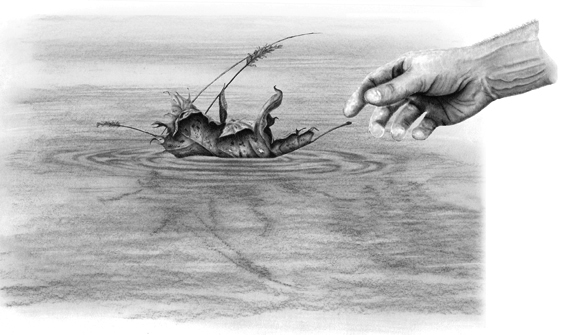

We built our own ships, there on the rim of a spring puddle, on the shore of our own tiny ocean. We built hulls from oak leaves, and masts from twigs and ferns. For sails we used beech leaves, and for rigging we plucked grass. Our ships were little and our cargo light and the decks were crewed by ants. On hands and knees we blew gently against tiny sails and sent our ships scudding out across dark water toward distant shores.

To a passing neighbor, it might have appeared that my mom and I were simply floating leaves in a puddle, but they would be wrong. Mom’s imagination was not bound by something so small as a puddle, and on that first day, when she took me in tow and said we were going down to the sea in ships, she meant it, and I believed it, and it happened. Mom could take a small idea, mix it with leaves and twigs, and turn the world into a tiny huge thing where a seven year-old boy could be wonderfully lost in the great expanse that was his own backyard.

We sailed for hours, Mom and I, out across the waves, with acorns bound for Portugal and pebbles bound for Ireland. Storms screamed in the rigging, we had chance encounters with whales, and across the galley tables slid steaming plates of gruel. Callouses grew on our hands. The backs of our necks turned cherry red. One day a man fell overboard while watching porpoises dance in our bow wake, and once we were lost for a week in a thick and dead-calm fog.

We sailed that spring and into the long summer, through the foggy doldrums of June and past the gales of September. The first snowflakes came in November and with them came the end of our season and our work so we tied up for good and returned to land.

“I won’t sail with ice in the lines,” Mom said, “Too unpredictable.”

So, I learned to be content with daydreaming and spent my afternoons third grade staring out the window, riding the waves of imagination toward far shores and longing for the spring rains that would flood the low spots in our driveway.

One day, during geography, my teacher asked if anyone knew where England was. While the other kids scrambled for the real answer, I just smiled and thought to myself.

It’s on the far side of a puddle in my driveway, next to an oak tree.

My brother and I used to shoot the rapids on the deck of the USS Oakleaf. Memories.